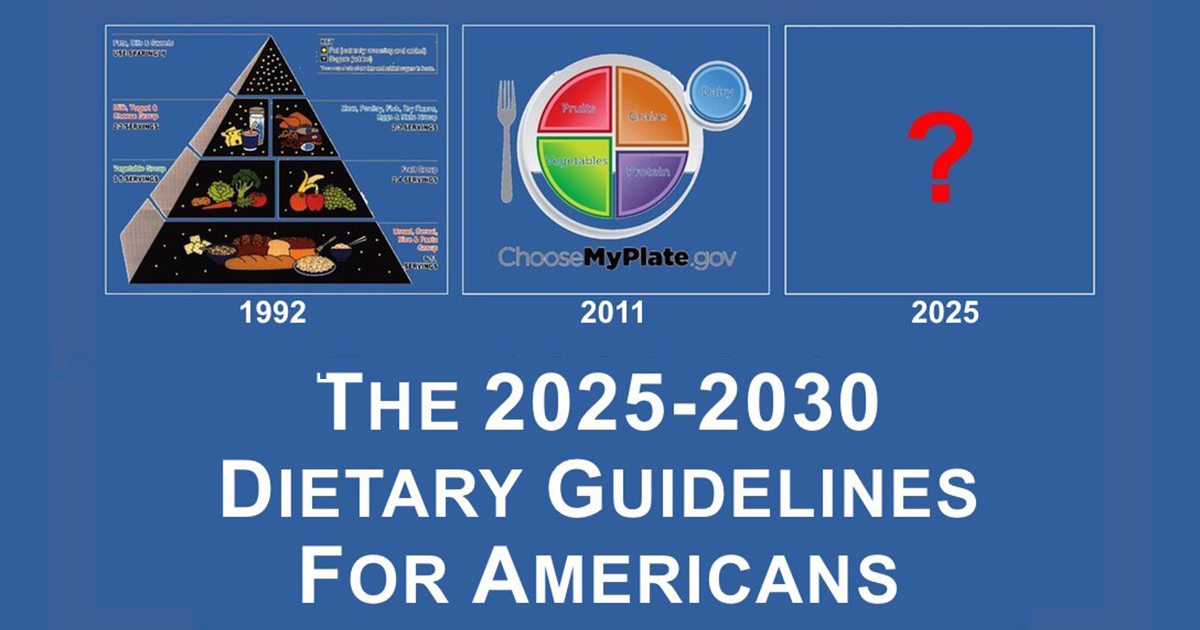

As the next edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) is set for release early next year, it’s an opportune time to reflect on an unsettling reality: for over 45 years, these guidelines have failed to achieve their stated purpose of promoting health and preventing chronic disease. Instead, rates of obesity, diabetes, and related conditions have skyrocketed. Why has the DGAs—a policy ostensibly grounded in science—so consistently fallen short? Let’s dig into the history, the assumptions, and the inherent flaws that continue to guide these recommendations.

A Brief History of the DGAs

The concept of government dietary guidelines emerged in the late 1970s when Carol Tucker Foreman, then an assistant secretary of agriculture, pushed for a set of standards to help Americans make healthier food choices. At the time, approximately 13% of Americans were obese, and by 1980, around 2.5% of the population had been diagnosed with diabetes, predominantly type 2 diabetes. Foreman believed that overconsumption was the root cause of these problems and urged nutrition researchers to provide their best interpretation of the available data.

In 1980, the first edition of the DGAs was published. These guidelines targeted “healthy Americans” and offered broad, seemingly reasonable advice: eat a variety of foods, maintain a healthy weight, and limit fats, sugar, and sodium. Over time, however, the focus shifted. By 2010, the guidelines expanded to address Americans “at risk of chronic disease,” which by then included more than half the population. Today, over 40% of American adults are obese, and nearly 10% have diabetes, with over 80 million Americans estimated to have prediabetes. Despite nine iterations of the DGAs, the trends have only worsened.

The DGA Paradox: Advice vs. Outcomes

Here lies the paradox: after nearly half a century of dietary guidelines, Americans are less healthy than ever. Is it possible that the very advice intended to prevent chronic disease has contributed to its prevalence?

From the outset, the DGAs adopted a plant-centric philosophy based on the unproven assumption that saturated fats—primarily from animal-sourced foods—cause heart disease. This led to the demonization of red meat and high-fat dairy while promoting carbohydrates as the primary source of calories. By 1995, the guidelines recommended that most calories come from grains, vegetables, and fruits, with an emphasis on vegetable seed oils (e.g., canola, soybean, safflower) over animal fats (e.g., beef tallow, lard, suet). Over time, the advice has evolved to endorse dietary patterns that prioritize plant-based proteins over traditional sources like meat and eggs.

Yet, as Americans followed this guidance—consuming more grains, vegetable oils, and plant-based proteins—the rates of obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases continued to climb. The USDA’s response? Double down on the same advice, blaming public noncompliance rather than questioning the validity of their recommendations.

The Circular Logic of the DGAs

One of the most significant flaws in the DGA process is its reliance on observational studies and dietary patterns rather than rigorous, randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Observational studies can identify associations, but they cannot establish causation. For example, the Harvard School of Public Health has long championed a “prudent” dietary pattern characterized by high intakes of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and low intakes of red meat and high-fat dairy. Not surprisingly, this pattern correlates with better health outcomes—but correlation is not causation.

Prudent eaters tend to be health-conscious individuals who engage in a host of healthy behaviors beyond their diet. They smoke less, exercise more, and have better access to healthcare. Conversely, those following a “Western” dietary pattern (higher in processed foods and red meat) are more likely to engage in less healthy behaviors. These confounding variables make it impossible to determine whether the “prudent” diet itself is responsible for better health outcomes.

The Shift to Dietary Patterns

By the early 2000s, the DGAs began emphasizing dietary patterns over specific nutrients or foods. While this approach may seem more holistic, it introduced a subtle but profound bias. Dietary patterns like the “Mediterranean” or “Healthy U.S.-Style” patterns were built on the same assumptions that guided earlier guidelines: that red meat and saturated fats are harmful, while plant-based foods are universally beneficial.

The adoption of dietary patterns allowed the USDA to perpetuate its plant-based agenda without addressing the growing body of evidence suggesting that animal-sourced foods can be part of a healthy diet. Instead, red meat, high-fat dairy, and processed meats were lumped together with sugar and refined grains into the “Western” pattern, ensuring that these foods were associated with negative health outcomes. Meanwhile, plant-based foods—even those high in seed oils—were deemed inherently “prudent” and promoted as healthier alternatives.

Asking the Wrong Questions

A critical flaw in the DGA process is the nature of the questions it seeks to answer. Rather than asking whether its recommended dietary patterns are more effective than alternative approaches, the USDA focuses on the relationship between existing patterns and health outcomes. This approach assumes that the recommended patterns are inherently healthy and looks for evidence to support that assumption. It does not test whether these patterns are superior to others, such as low-carbohydrate or animal-based diets.

For example, what if a diet rich in animal-sourced foods and low in refined grains and sugars is healthier than the predominantly plant-based patterns promoted by the DGAs? Without RCTs comparing these approaches, we cannot know. Yet, the USDA continues to build its guidelines on observational data, ignoring the potential harms of its advice.

The Way Forward

If the USDA is serious about promoting health and preventing chronic disease, it must adopt a more evidence-based approach. This means:

-

- Conducting Rigorous Trials: Fund large-scale RCTs to test the efficacy of various dietary patterns, including those that prioritize animal-sourced foods.

- Reevaluating Assumptions: Question long-held beliefs about saturated fats, red meat, and dairy in light of emerging evidence.

- Incorporating Diverse Perspectives: Include researchers and practitioners who challenge the prevailing plant-based narrative in the DGAC.

- Addressing Confounding Variables: Design studies that control for socioeconomic, behavioral, and other confounding factors to isolate the true impact of diet on health.

Conclusion

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans have become a case study in the dangers of circular logic and confirmation bias. As the 10th edition approaches, we have an opportunity to demand better science and more transparency. After nearly 50 years of poor outcomes, it’s time to stop doubling down on failed advice and start asking the hard questions about what truly constitutes a healthy way of eating. And as the health of future generations depends on it, there is no better time than right now to become your own health advocate.

When the DGAs encouraged the consumption of trans fatty acids, I was among the trailblazers who said to avoid them. Fast forward, the day came when the FDA banned them, and they are no longer included in the DGAs. Today, we face another critical challenge: the overabundance of vegetable seed oils and the detrimental effects of skewed Omega-6 to Omega-3 ratios. A growing body of evidence underscores that a significant factor in our ongoing health crisis is the widespread deficiency of quality Omega-3s in our food.

You don’t have to guess about your health. Take charge of your well-being today. Schedule a free consultation with me to learn how you can optimize your Omega-3 intake and achieve a thriving quality of life. Together, we can pave the way for better health and a brighter future.

References

-

- Teicholz, N. (2023). “The Evidence Gap in Dietary Guidelines: A Critical Review.” Unsettled Science. Retrieved from https://unsettledscience.com.

- Willett, W., & Hu, F. B. (1999). “Dietary Patterns and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(2), 423–431. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.2.423

- Foreman, C. T. (1996). “The Origins of the Dietary Guidelines.” Interview conducted by G. Taubes. Personal archives.

- Annals of Internal Medicine. (2020). “Systematic Reviews of Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease Risk.” Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(9), 636-645. doi:10.7326/M19-1708

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Washington, D.C.: USDA.

- National Cancer Institute. (1993). “Dietary Patterns and Cancer Risk.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2(3), 187-192.

_______________

🗓️ Schedule a FREE consultation with Robert Ferguson about becoming a client: SCHEDULE FREE CONSULTATION

👉🏽 To order ONLY the BalanceOil+, > CLICK HERE

👉🏽 To order the BalanceOil+ with the BalanceTEST, > CLICK HERE

👉🏽 Watch a free online presentation on the BalanceOil+ and the BalanceTEST: WATCH NOW.

_______________

Robert Ferguson is a California- and Florida-based single father of two daughters, nutritionist, researcher, best-selling author, speaker, podcast and television host, health advisor, NAACP Image Award Nominee, creator of the Diet Free Life methodology, Chief Nutrition Officer for iCoura Health, and he serves on the Presidential Task Force on Obesity for the National Medical Association. You can e-mail Robert at robert@dietfreelife.com.

0 Comments